‘The Typing Man’ short story explores Turkish-Arabic names in the context of composing private letters in public spaces. Shortlisted in the Mslexia Awards, the story was selected from over 2,000 submissions.

The story was inspired by a scene witnessed in a park near the Blue Mosque in Istanbul. A woman and a man faced one another across a fold-out table. A manual typewriter and set of papers conveyed a sense of formality. With the law courts just down the road, this appeared to be an official transaction.

In spite of the ubiquity of mobile phones, internet cafes and personal computers, why was there still a need for a man (the typist) to mediate the message the woman wanted to communicate?

What if, one day, the business conducted in that public park did not fit the usual pattern of work for the typing man, but was about something much more personal?

With a flight of imagination and some research, the story of a man mediating the words of that woman in an Istanbul park took shape.

![]()

Buy a copy of ‘The Typing Man’ eBook

![The Typing Man by [A. T. Boyle, Gül Turner]](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51BxALE90aL.jpg)

Look inside the book by clicking here …

To buy a limited edition book printed in Cumbria in Northern England featuring original illustrations, email exObjects2022 @ gmail.com

There are a some typing women in the world. The people who type for others, because they don’t own a typewriter or computer or cannot read or write, are mostly men.

This trio sitting on a bench outside a Rwandan bus station typing business papers and CVs consider themselves fortunate when they are given commissions to type up fiction and plays. Requests to type a love letter, fairly common in the world of public typists, represents perhaps an even greater position of privilege.

When the women see the police coming, they disappear with their tables and typewriters, because street vending in Rwanda is illegal.

Marie Gorette Nimukuze, one of the Rwandan women typists, says: “It’s very confidential what we do, we never tell people what we’ve written. When people ask us to write letters there is a trust there and we don’t break it.”

Symmetries can be found between these women’s recollections and the character of Rauf Osman in The Typing Man book. Here are some of the observations made by another trade in the outdoor square, the peanut seller Aziz Nesin:

page 15 of The Typing Man written by A.T. Boyle

page 15 of The Typing Man written by A.T. Boyle

Turkish-Arabic names

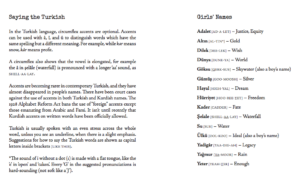

A key reason for creating The Typing Man was to increase the understanding and appreciation of a minority culture in Britain. The sounds and meanings of names given at birth in Turkey, and the way they are spoken, are incorporated into the text.

The names people carry round with them can be heavy with import. They may be perceived as ennobling, aspirational, and sometimes a put-down. The Turkish girl’s name Kader [say it: CADDER] means Fate, and the boy’s name Devrim [say it: DEv‒RIM] means Revolution.

pages 36-37, The Typing Man written by A.T. Boyle

pages 36-37, The Typing Man written by A.T. Boyle

Creative letter writing inspirations

Here are some of the questions the author and translator posed:

Q. How might someone who stands between the message and its form of expression alter the content of a letter?

Q: Does status derive from the Typing Man’s role as interlocutor, the mediator of other people’s messages?

Q: Should a character’s name always convey something important about them?

Q. Can a person’s name change who someone is?