by Smita Tharoor

“There are ghosts that dwell not in shadows, but in sunlight.

They live in the cadence of your laughter, the way you stir your coffee,

the phrases you borrow without thinking. They are the echoes of those who shaped you, loved you, and left their fingerprints on your soul—even if they’re no longer here to hold your hand.”

These are the opening lines of a poem from a collection written by Daniel Ryan and Ila Sharma which I happened to read a few days ago.

Many years ago, my son and I volunteered for a Proustian experiment on smell. We joined a small group of around 30 people. We were put into groups of four or five. We were given one box at a time which we had to open to smell. After smelling it, we needed to write down our memories, identify the smell and discuss in our group. How very differently each of us reacted to the smell. I remember correctly identifying burnt tar and being transported to 1975, a hot summers’ day in Calcutta where the heat had melted the roads surface. The car beeps, the cries of the hawkers. My London born son had no emotional reaction to that smell.

Whether it is holding a madeleine and anticipating its taste, smelling something in a box that transports you to another country and time, or reading a poem about ghosts that live in us; what I find powerful is that we all have our stories, our narrative. Our memories define and influence us in all that we do.

My parents were born in Kerala. Deep in a remote village is our ancestral home where my maternal grandmother was born and lived until she died in 2015. Every childhood summer and when I was at university, we went home to my grandmother’s home.

It is only on reflection that I have come to appreciate how these experiences shaped me. I was a genuine diasporic Indian, one intimately connected to the west, east, north, and south of India. I was used to a busy bustling city with showers in the bathroom and running water from a tap, travelling by car to my destination. I was also comfortable taking water out of a well, bathing in the river and travelling to the local cinema on a bullock cart. I was born in Bombay, grew up in Calcutta, went to university in Rajasthan and come from Kerala.

I grew up with a multi-dimensional identity that embraced the traditions and poetry of Kerala alongside morning prayer at school assembly run by Irish catholic nuns in the chaos of the then Bengali communist city, Calcutta. My childhood memories are of hearing the mridangam being played by my father alongside songs by Malayalam singer, Yesudas by mother. Meanwhile my sister and I were dancing to the Beatles. I also remember hearing a Malayalam poem, an Ottam Thullal that my father recited about his time when he lived in London.

My father, Chandran Tharoor was born in December 1929 in a remote village, Chittalanchery in Pallakad, Kerala. He was the sixth of eight children. His father died when he was eleven, leaving his eldest brother at the age of twenty-four, to be the male head of the household to financially support and educate the family.

My uncle took his responsibilities seriously, worked hard and managed to arrive in London in the early Forties to earn a wage and support his younger siblings and elderly mother. In July 1949, he sent tickets for my father aged nineteen to travel with his two younger brothers, by ship to Liverpool and onwards to London.

His world could not have been more different. This was post-war London, rationing, cold and damp, pushing coins in the meter for heating. He had left a village with no electricity, carrying water from a well to have a bath, temperatures that never dropped below 25c. The talking point of excitement would have been seeing many goats running through the centre of the village to be herded for grazing or slaughtering.

His only language was Malayalam which naturally did not take him very far in London. But my father was a curious man, an observant man. He was also young, handsome and nubile. London was a treasure of experiences and charm that he had never savoured in his village in Kerala.

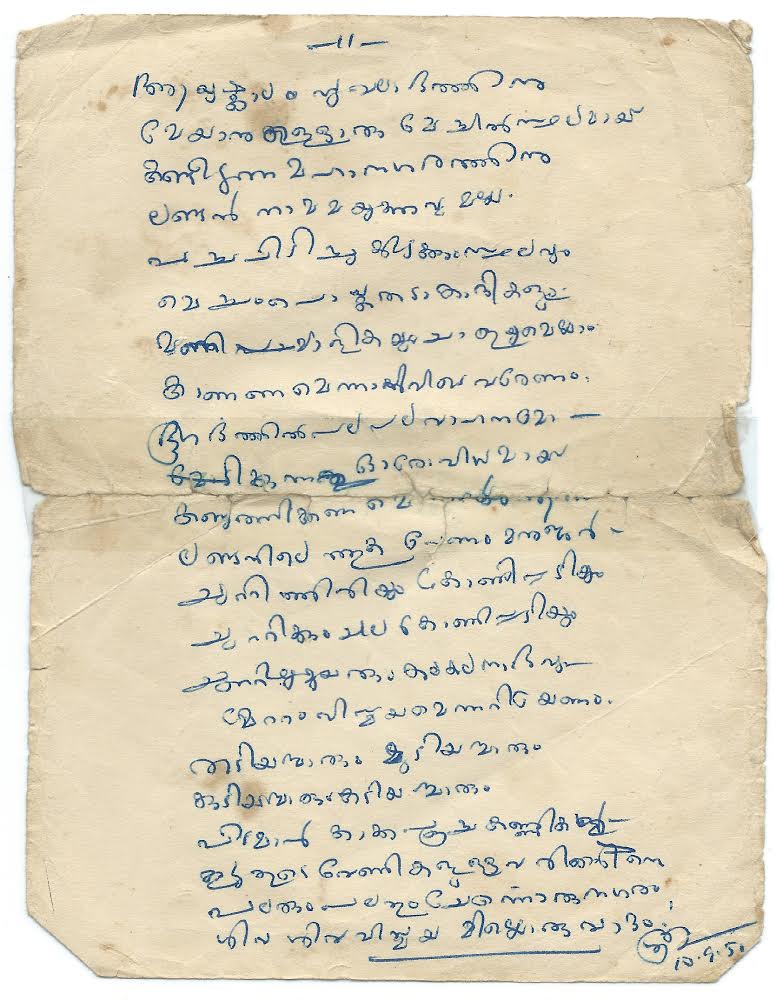

He was part of this new society and at the age of 21 in September 1951, he sat down at the Indian Students Bureau on Exeter Street just off the Strand in London and wrote an Ottam Thullal, gently raising questions on the prevalent society and the behaviour of the English. What is ironic is that 74 years later, many of these behaviours still prevail in the London that I now call home

They say “thank you, thank you” for everything small,

And “sorry, sorry” when things go wrong at all.

My father moved back to Bombay in 1958, where I was born. Growing up, I was regaled with stories of his decade in London. The friendships he made, the customs and culture he learned from the English, their strange idiosyncrasies, their sense of humour, the awful weather, the pea soup fog that prevented him from seeing his stretched-out hand. He loved London and its people. He did not feel racism. If anything, he and subsequently my mother were seen as curiosities.

My father told me about his Ottam Thullal that he had written and performed in 1951. The original handwritten script is 11 pages. The performance, of around 30 minutes, was at the India Club, Craven Street, London in front of an audience including the first High Commissioner to India and founder member, Mr Krishna Menon. This was the only time that my father performed it in public. My father died in 1993 and sadly, the India Club closed permanently in 2023.

When my siblings and I met for our father’s funeral, it was agreed that as I was the person now living in London, it was fitting that I have safe keeping of the original writing in my father’s hand.

An Ottam Thullal is a recite-and-dance art-form of Kerala. It was introduced in the eighteenth century by Kunchan Nambiar a prominent 18th century Malayalam poet.

Legend has it that Nambiar, fell asleep while playing the drum for a recitation, inviting ridicule from the presenter. In response, Nambiar developed the Ottam Thullal, which raised prevalent socio-political questions and made a satire of human pedigrees and prejudices. Social criticism wrapped in humour was the hallmark of his work.

Today’s modern stand-up comedian was in Kerala a long time ago. My father used this approach of in his Ottam Thullal in describing the Londoners.

Oh, how I wish Kunchan Nambiar were here,

To describe this grand old London for us, dear.

But alas, we’re not so lucky, you see,

To hear such tales from Kunchan Nambiar’s glee.

But no worries, friends, I’ve made my way here,

And I’ll tell you all that I’ve seen, loud and clear.

Whether you like it, fine—if not, that’s okay,

There’s plenty to share, so let’s dive in today.

Once upon a time, in the sea’s embrace,

Indra glimpsed Dhwaraka, a mystical place.

He thought, “Why must Krishna have all the glory?”

So, he conjured a city—now that’s a good story.

Oh, those lucky ones who make it here,

Reborn as humans—no need to fear.

Worldly delights? Come here, my friends,

This city’s charm never ends.

Many have come to this foreign land,

Iyenkars, Panikkars, Nairs, and others so grand.

Menons, Nambiars, Chatterjees too—

Some with servants, others with pots, it’s true.

Tilak, Gandhi, Gokhale, and more,

Roamed these streets, and what’s in store?

Being “London-returned” gives you some clout,

Back home, it makes you stand out, no doubt.

The tales are endless, I could go on forever,

But let’s move on now—couldn’t leave you waiting, clever.

I set my heart on reaching this place,

But delays made me sigh, oh such a chase.

Twisting my moustache, with resolve so tight,

A month of travel—finally, I made it right.

Words fail me now, friends, to describe this scene,

You have to see it, or just take my word—it’s serene.

And once you’ve heard my tale, please forget,

For if a Londoner hears, I’ll be in a tight set.

They say “thank you, thank you” for everything small,

And “sorry, sorry” when things go wrong at all.

Brushing teeth, scraping tongues—it’s routine,

Bathing too, though some may find it obscene.

Some clean with spit, some with paper, what fun.

Oh, the changes I’ve seen here, one by one.

Bread, bread, and more bread for every meal,

Toast for breakfast, lunch, and dinner too—what a deal.

Cheese on toast, sweets, and coffee to end,

And tips for the waiter? Always, my friend.

If you’re looking for food that’ll make you feel full,

The shop windows make you want to pull.

If you’re tired of veggies, meat’s in full swing,

Fish, chips, sausages—oh, the joy they bring.

Some dishes, I must say, might be a fright,

Not everyone’s taste, but that’s alright.

Knives, forks, and spoons all ready to stab,

But oh, how we thank the ones who made them fab.

And wouldn’t it be lovely, just for a change,

To have rice and sides that are truly strange?

Now, let’s peek at the streets, but don’t be shy,

It’s hard to tell who’s who, don’t ask me why.

Faces so pretty, with hair all unique,

But I’m no poet—I’ll just take a sneak.

Some with eyeliner, some with lipstick bright,

Some in hats like frying pans, what a sight.

Others with dresses that leave little to the mind,

But I’ll stop here, friends, it’s not the time.

Shops galore selling tobacco with glee,

One after the other, it’s quite the spree.

So many festivals, history galore,

“Whatever it is, it’s mighty,” who’s keeping score?

If I shared these sights with my master at home,

I’d probably be sent packing to roam.

Couples everywhere, like cattle in a herd,

Boys with girlfriends, girls with boys—so absurd.

They’re stitched together, no words they say,

Except for “I love you,” all day, every day.

Let’s peek inside the bar—whisky, brandy, and more,

Endless drinks to adore.

The rich sip wine, the poor sip their beer,

And if you’re not drinking? You might feel a tear.

Some stay for the charm, the green lands, the fun,

In London, there’s always something to be done.

From grand lakes to houses both big and small,

To truly experience it, my friends, come and visit it all.

My father and I arrived in London at the same age, but Eighties London was very different from London in the Fifties. Gone were the pill box hat, stockings and dresses. Yet not much else had changed. The English, their habits and their customs. I have now acquired them, and I say sorry and thank you at any given opportunity.

My fathers’ Ottam Thullal gave me a window to a London that I did not know I would be living in. I had first heard it as a child allowing me to imagine a faraway land with unusual customs. But far more importantly, it gave me a constant connection, a reminder, a tie to my father who died too soon.

In November 2023, my son married his beautiful bride in our ancestral home in Kerala. I wanted our guests from the UK to appreciate our heritage and customs. What better way was there than having my father’s Ottam Thullal performed. But this was more than a mere performance. In 2018, I had reached out to someone, Dr Kuriakose in the UK to ask if he knew of someone who could perform my father’s Ottam Thullal at the India Club in London. For one reason or the other, everyone got busy, and it was forgotten about.

In June 2023, totally out of the blue, Mr Kuriakose contacted me with a WhatsApp recording of someone reciting my father’s satire. I had not been in touch with him since 2018. Mr K did not know that my son was getting married or that we were actively searching for someone in Kerala to perform it. It felt like it was a blessing directly from my father.

We had about 200 guests at the wedding who all received a printed English translation that they could refer to as the artist, Maruthorvattom Kannan and his team performed. I remember sitting in the front row, tears streaming down my face, holding my son and my husband’s hands on either side of me as my father’s words came alive. For the first time, 30 years after my father’s death, his words came to life again.

These are the emotional ghosts we carry—not as burdens, but as sacred heirlooms.

They ache, yes. But oh, how they glow.

They remind us that love outlives time, distance, even death.

That to miss someone is to honour how deeply they mattered.

So today, let’s speak their names into the light.

Whose ghost do you carry gently?

Is it a melody they hummed, a recipe they swore by a stubbornness you inherited?

We are all mosaics of those we’ve loved.

Their shards live in us—sharp, shimmering, and unbreakable.

(by Daniel Ryan and Ila Sharma)

Chandran Tharoor, my father, I still miss you so.

About the story

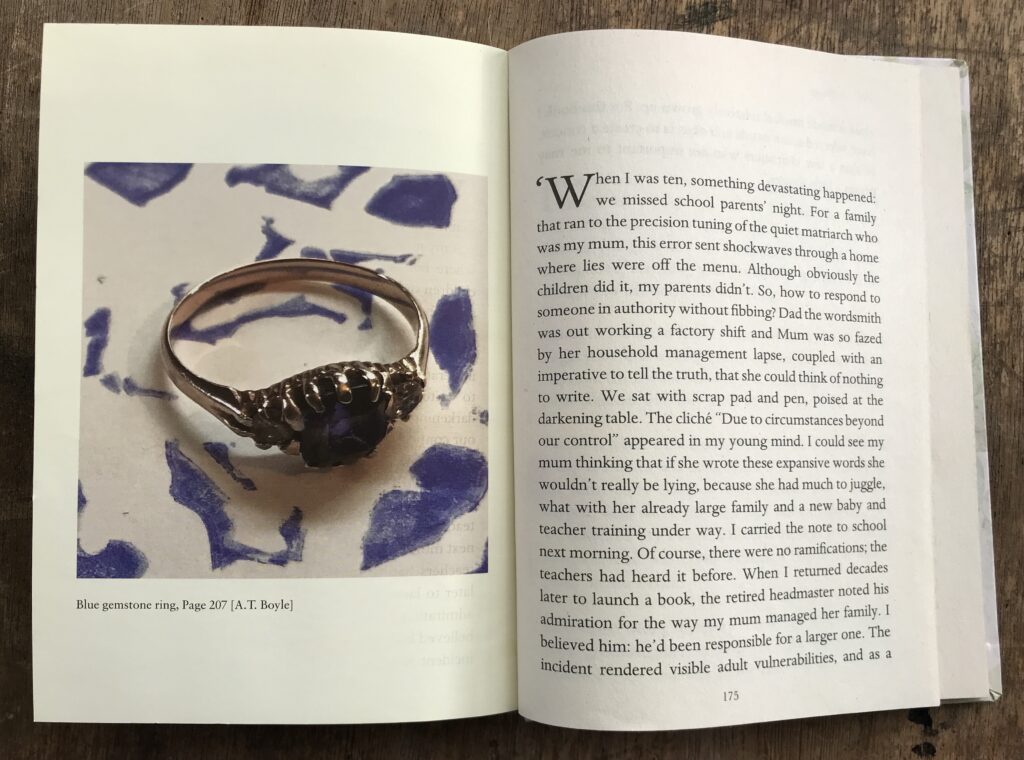

This satirical poem handwritten in the Indian language of Malayalam in 1951 was performed at the wedding of Smita Tharoor’s son. Revisiting her father’s work for Writing that Sings, Smita was able to value this gift from her father across the decades.

About the authors

The Ottam Thullal, intended to be danced to, is by Chandran Tharoor, shown here at the age when he wrote his poem on arrival in London.

For her podcast Stories Seldom Told Smita Tharoor has interviewed people round the world and shared their life-lessons on how they surmounted barriers. The podcast is heard in 107 countries and ranks in the top 5% of podcasts globally.

Smita’s podcast recording of A.T. Boyle will be published later in 2025.

(copyright Smita Tharoor, 2025)

____

Thanks to Shinie Antony, director of Bangalore Literature Festival, for highlighting the importance of the Keralite artform of Ottam Thullal. Shinie is co-editor of the first exObjects book the art of holding on, letting go with A.T. Boyle.

________

To read the other 5 commissions in Writing that Sings click here