by A. T. Boyle

If his life was a surprise to him, his ending was a surprise to me.

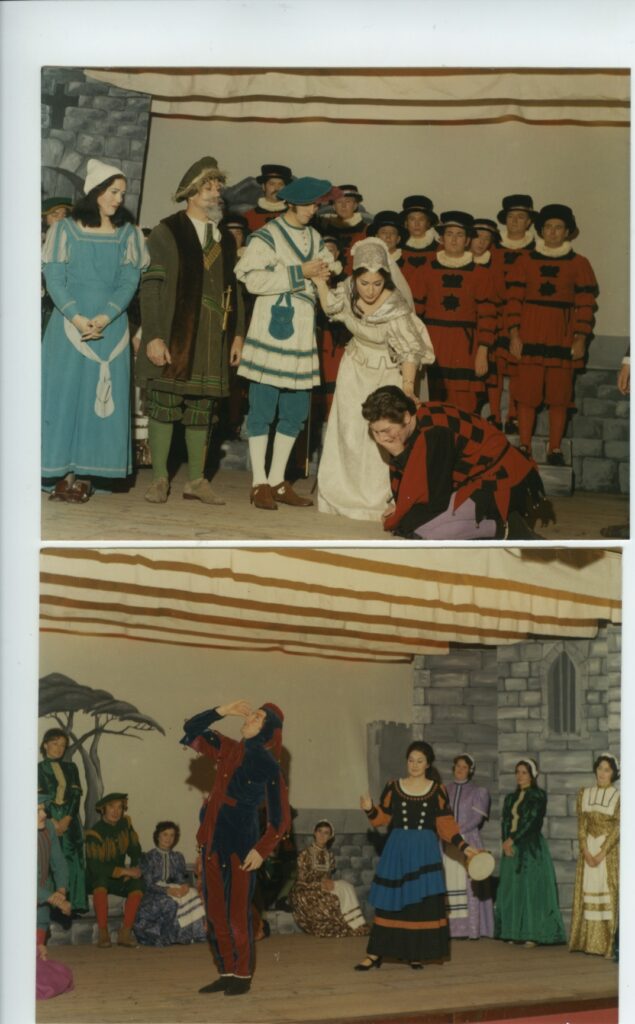

‘The Yeomen of the Guard’ by Gilbert & Sullivan

If you wish to succeed as a jester, you’ll need

To consider each person’s auricular

What is all right for B would quite scandalise C

(For C is so very particular)

So said Jack Point the jester in Gilbert and Sullivan’s The Yeoman of the Guard, a role my dad played more than once. I’d come to wonder why, particularly given the last words he said to me. Or more precisely, the way he uttered these two words the day before he died.

Although I could be doing locals a disservice, I doubt many Preston families in the 1970s were debating whether the world was witnessing A) a seismic socio-cultural shift or B) a short-lived self-indulgent craze. But such cosmopolitan ideas from the heady Aesthetic Movement of the 1870s found their way into my Lancashire sensibilities and validated my own imaginative life through the operatic scenes of Patience.

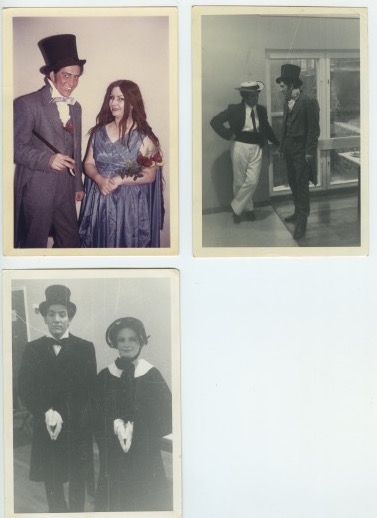

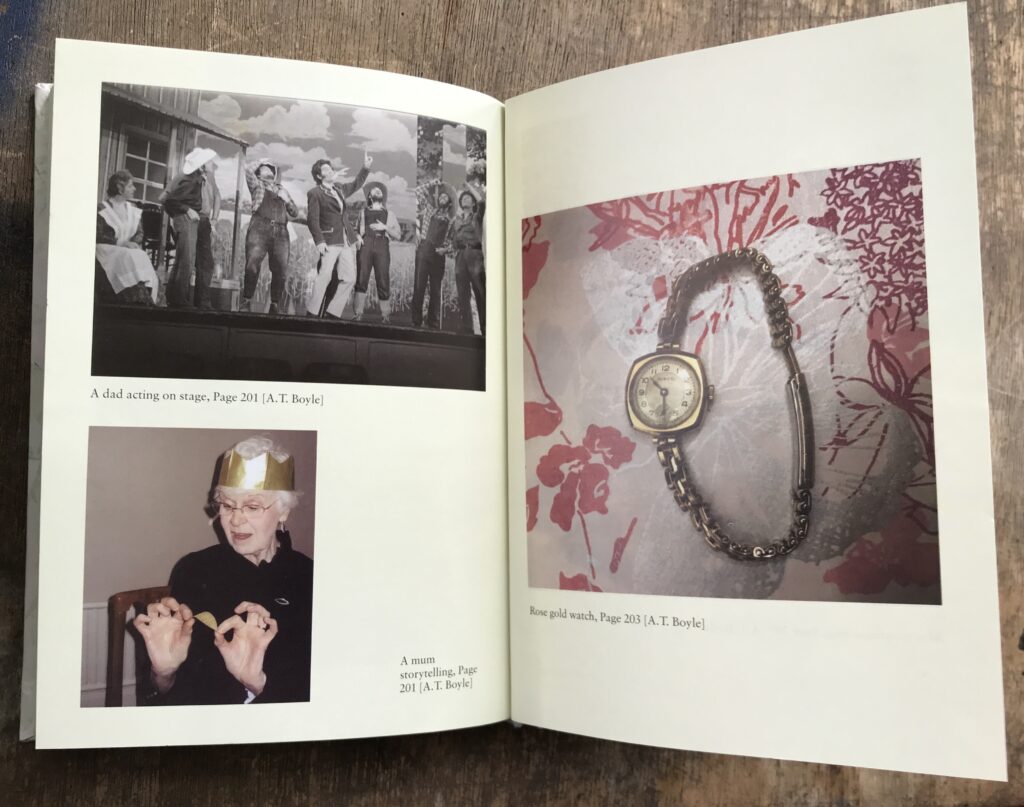

As Dad roved in jester’s garb through a sixteenth century Tower of London, it didn’t matter that we had never physically been to that city or happened to be living at that time. Amateur dramatics allowed us to travel beyond the walls of our born-into lives.

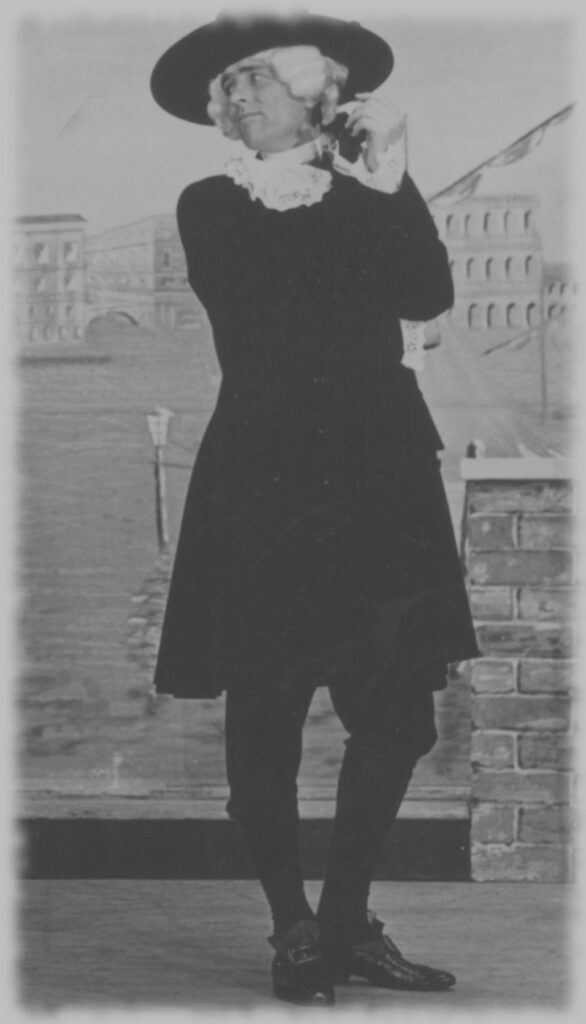

The wide-brimmed hat and lace ruff and sleeves of Don Alhambra Del Bolero suited my dad to a tee. But no time to tarry, because a Cornish baddie in the early 1800s came calling from the world of Ruddigore. And 1750 Venice of The Gondoliers made a refreshing change from holidaying in Blackpool, or Ireland where his aunties and uncles lived.

Dad started performing young. A Methodist youth club run by a socially enlightened vicar provided a small hut and practical opportunities to encounter worlds beyond the lads’ factory-laden lives. Acting was just one of the skills they learned, alongside scene-painting, stage make-up, costumes, production, singing.

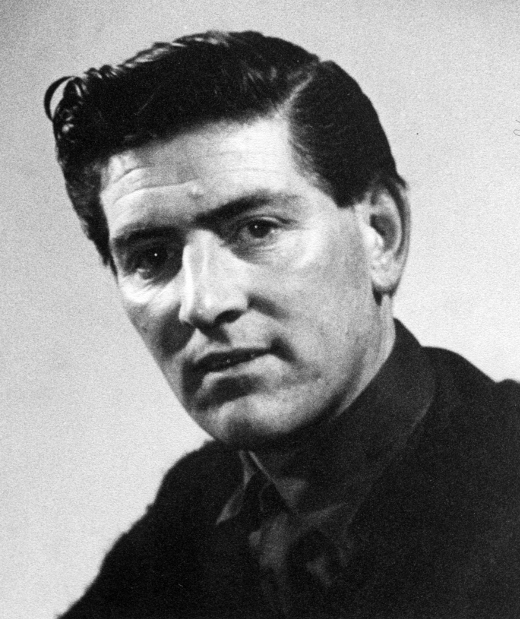

His first teen role was speech-only, a drawing room farce far from the two-up two-down rented mill homes where he and his gang lived, up Acregate Lane way. But he appears to have inhabited the part. Shoulders square, Dad stands confidently on the She Stoops To Conquer stage looking way older than his nineteen years. He would act a lover before he secured a proper lover, and play dastardly dudes when as far as I could tell all he’d got up to was a few pranks round town.

Over the next quarter century he would delight in flamboyant laced cuffs and collars and lush velvet hats and leather buckled boots the like of which he could only access via the vicar, who accessed them from the wardrobe mistress of the adult G&S company nearby. Dad would enthusiastically don costumes in fabrics and designs representing a dizzying sweep of social history. Here was a grand opera likeness of a more limited reality. Suppressing his mop of Brylcreme-quiffed hair under cotton wool wigs probably required a few strategically placed Kirbygrips borrowed from my mum’s roller set.

There’s a studio shot of Dad as Grosvenor, marketing Gilbert & Sullivan’s Patience. Dolled up in what looks like a plush mohair jumper of some quality and a black real silk shirt no one in our milieu would have worn, Dad peers out indulgently – not merely encompassing the photographer in the same room, but the whole wide world. He’s super-ready to autograph his photo for fans, and I can sense how easy it was for him to act the aesthete.

I’m awed by the efforts of the wardrobe mistress too. Season after season Mrs. M. Cairns and volunteers pulled off rather good costumes that eased the audience’s travel through all geographies and periods and social strata. Sometimes hired from costumiers in Edinburgh, I’m guessing the economic model was a minimum 100% seat capacity.

‘I am a trustee for Beauty,’ Grosvenor declares in a surprisingly endearing fashion, ‘and it is my duty to see that the conditions of my trust are faithfully discharged.’

I’m heartened by the plucky rejoinders penned by Gilbert for the dairy maid Patience, a combination of innocence and perverse logic that explains why she cannot love my dad: ‘Oh if you were but a thought less beautiful than you are.’ Recently, a cultured Londoner who used to be married to a Hollywood film-maker stopped in her tracks when she saw the photo of Dad as Grosvenor. ‘He looks like a Hollywood star!’ I had to agree, and I wish I’d told him. Even if it would have sounded weird.

I’m assuming that when Dad applied ghoulish make-up to play the wicked baronet Sir Despard Murgatroyd in Ruddigore he was channelling darker parts of his own personality. The publicity and backstage shots in the family theatre album are a bit of a mishmash, but they reveal the collegiate atmosphere of a performing troupe, and that thought has been put into the way one holds a smart cane and absorbs the unfamiliar architecture of a character’s mouth.

Through Victorian theatrical fluff this was Dad interrogating a few essentials of human nature and reflecting them back. I’m convinced that Jack in The Yeoman of the Guard is the closest to him, a jester who wears his heart on his sleeve while shape-shifting and plotting. Dad will veil his limitations, pivot to survive, cry, dance, laugh, empathise, seek sympathy, and with a spring in his step persuade others to join in his dance.

For, look you, there is humour in all things, and the

truest philosophy is that which teaches us to find it

and to make the most of it.

Though we did borrow children’s books from the library, a full collection of linen-bound illustrated books by a Victorian author were the only ones I remember on the shelf. Lyrics penned by the G in G&S contained ideas my dad eagerly embraced, and while busy slinking and sinking in the Tower of London’s shadow he was summoning Artful Dodger qualities from a Charles Dickens ink.

I don’t know how many times my dad got married. I suppose I could calculate it from the number of roles containing that storyline and the number of repeats he did of that role. Rehearsals must have been hard on top of night shifts producing artificial silk (which paid better than 9 to 5), but he was having the time of his life. My mum, the real person he was married to, enabled his imagination and more or less forgave the swerving of washing up. At least in Patience he was the Idyllic Poet rather than the Fleshly one. I can imagine Dad enjoying this romantic quippery with the dairy maid:

I have loved you with a Florentine fourteenth-century frenzy

for full fifteen years!

When playing Strephon in Iolanthe Dad wasn’t required to present a simple shepherd. Instead, as specified in the script, he must be an Arcadian Shepherd who thankfully by the end will be sporting that familiar starch-white ruff. And he’s able to marry for love (Phyllis this time), once the Fairies step in. The Gilbert plot perhaps caused my dad to read A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which became his favourite Shakespeare.

I can imagine him diving with glee into the conundrum of youthful Archibald Grosvenor who in Patience transforms into a commonplace everyday young man (which most of 1968 England would already consider him to be). He finds love only because he is imperfect. So what joy to inhabit the character of someone who pitches from high to low strata, aspirations and reality equally validated. A character etherealised and idealized in a feelgood opera.

Dad sometimes expressed irritation that by default the tenor secured the lead parts, considering himself the better actor. As a baritone unable to reach the notes laid out by musician Arthur Sullivan, the company’s main tenor possessed such a dulcet voice that everyone forgave his wooden dialogue.

The women in the cast were often called ‘ladies’ and bunched together as adoring harmonisers for the male chorus. In Patience six women play Rapturous Maidens, but the dairy maid is thankfully a feisty woman who debunks the idyllic poems spouted by my dad and the older aesthete Bunthorne (he of Castle Bunthorne). This ‘lead’ actress appears right at the bottom of the printed programme listings.

I’m convinced Dad approached each part with a healthy curiosity about these worlds someone else had fashioned, that required clothes and foibles he must not only wear, but convince the audience he feels at home in. I don’t remember him wearing any of those clothes at home. Not even the tights. A bit of a shame.

The standard five consecutive show nights sold out quickly, aided by the community patronage structure. I was always fascinated by the way my dad kept a beady eye on Bob Bamber’s baton and praised the musical director’s skill; the orchestra however was sometimes criticised by an otherwise supportive regional press. The printed show programmes cram in over a hundred subscriber names, people who kept the company afloat for decades in inner city Preston. Just round the corner from my school, here was a microcosm of the funding model that kept the grander arts buoyant in London (and perhaps Venice too).

When we’re children we get taken places. As teenagers we question our parents’ behaviour even when it isn’t questionable. Still, fresh into secondary school I invited my new best friend Eileen to Rogers and Hammerstein’s The King and I at the Little Theatre in Southport, a grander venue than his regular playhouses. My dad is in the title role and I’m feeling silently proud of him. In super-quick time he’d acquired the speaking and singing parts and their already-rehearsed dramaturgy, stepping in for the lead who was ill. In those two weeks he also managed to squeeze in a visit to the barber. The resulting skinhead so offended my mum that, in spite of loving him more than the social conformists she was bowing to, she refused to be seen in public together until his usual thick locks grew back.

On stage, having willingly swapped the uniform G&S tights for bare legs and an ankle chain, it had been a more taxing decision to trim his signature sideburns, which rivalled the contemporary Chennai-born balladeer Engelbert Humperdinck.

My friend Eileen confessed in the interval, without blushing, that she totally fancied my 43 year-old dad. I had no idea how to respond. Which was unusual for me.

Eileen was quite advanced and had read The Lord of the Rings trilogy at least twice. Still, her comment was hard to fathom. I recall the discomfort of sitting next to her through the second half. But something did make sense, how men and women were drawn to my dad, his open smile, his obvious interest in them, that precocious imagination and chutzpah. From an early age he had leaned in to the clever word dances and plots of librettist William Schwenck Gilbert in addition to the cigarettes. On cigarettes, instead of giving up entirely he switched to smoking one cigar a year, abandoning the habit when the health facts became indisputable. I reckon those stage parts planted the notion that Dad could lead others astray just as he had willingly wandered along the lyrical pathways of light opera and explored the benefits of smoking for social cohesion.

His stage roles will have helped him to dream up alternative realities. Job promotions did present themselves from time to time, but this would only be acceptable if our family moved with him. A new artificial silk factory in Belfast was decided against because it was the height of The Troubles, and Canada was rejected because we’d be abandoning my grandma just after my granddad had died. She was considered too old to move to another country, having for seven decades roved the same Preston neighbourhood. Once made, a decision was not revisited within our earshot, though I can’t believe these fleeting chances to experience different cultures didn’t occasionally cross my parents’ minds.

Dad was not simply the happy-go-lucky lad who’d acquired a few quips to catch the ear and eye and heart. It required dedication to become a self-serving shape-shifter with a heart-rending simper I hear now as I heard it as a child. If he was ever ruthless, it was in honing his communication techniques. The Yeoman of the Guard jester is not merely a performance but an expression of Dad’s devotion to intensity. In a vast Victorian hall lacking tiered seating all necks crane towards the stage, our ears latched to those sobs.

Soon enough he will drop his head to toll the sad bells on a tricorn hat that rang happily before. Emotion will audibly drip from his tongue but the show reviews will not call his style hammy. The rapt audience must accept there will be no reprieve from this love-lorn torment, but our collective hope for actor, singer, father is that he will not leave our world entirely.

As the velvet curtains tremble on their cords we silently plead for this story to end well. We all know the ending, but until we see it, three hundred hearts varying in robustness will pulsate in unison as Jack drops senselessly to the boards. The curtains will begin to enact their dreadful purpose, to shut us out, and in these final moments a woman with a different name from my mum will proffer sympathy, though her decision is already made.

Mum’s here with us, ten rows back, young children at her side. I glance at her profile. She too is wondering at this wise fool whose heart bleeds, who has devastated us.

When the curtains rise again, surely the jester’s despair will have been wiped away by a warm flannel. Surely this broken man will come home to the 1950s semi on the housing estate where he belongs.

By the time I emerged as a critical teenager Dad had moved on to writing storylines and lyrics for contemporary musical plays, lots of poetry, and directing a couple of amateur companies. By then I had thoroughly turned from G&S. When we sang together in public I’m convinced all eyes were on him. The timbre of our voices harmonised well, and it was our way to connect. The ability to phrase was his. Though he worked feverishly on every line, every stage direction, his later creative output enjoyed few readers and audiences. This is the part I play – sometime mediator, sometime enabler.

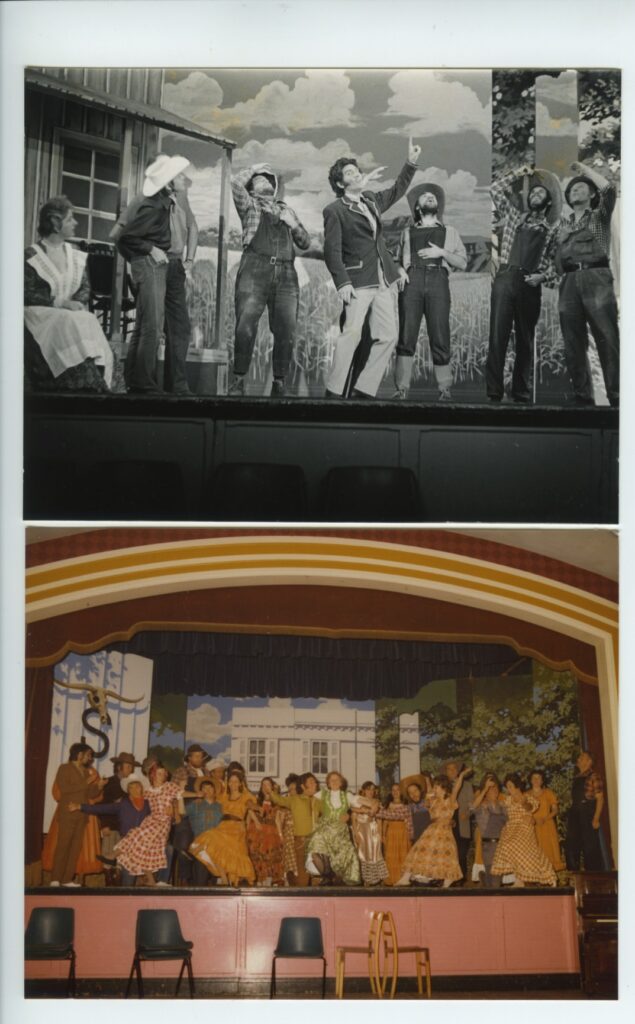

Alongside the familiar textile samples he conjured names for in the Courtaulds laboratory and the undervalued theatre albums is a new-found object: a personal diary. This record of his second ever job I discovered in the final moments of leaving my parents’ home after their deaths. Hidden in plain sight on the back bedroom shelf, an almost daily account of how Dad supported disabled adults at a Preston Day Centre.

Towards the end is a scattering of newsprint poems roughly pasted in. One is an account of a reunion of factory workers. More than anything it shows me how Dad elicited the emotions of his listeners. Exactly a year since the giant gates shut them out, most having started there as teenagers, erstwhile close-knit colleagues are re-uniting for the first time.

Hesitant greetings carefully measured in forearm lengths

tenuously bridge last year’s reluctant partings.

The almost-strangers stand awkward as poseurs,

aged caricatures of their new-starter roles.

Forgotten are the foibles,

the once formidable barriers now

time-eroded to insignificant obstacles.

In that first handshake is my dad’s pared-down analysis of what sits beneath the surface of devastating mass redundancy, a means to survive lost in the morass of early Eighties unemployment. There is recognition that every person in that room, including himself, has turned up scarred, but they’ve turned up.

His poem takes the reader’s arm, guides us smoothly towards a vision of what can be salvaged in a still jobless present for some. This is an invitation to sit again at the centre of the scene. He peppers the scene with theatre jargon, poseurs, roles, caricatures, mention of foibles. These are smiles-in-spite-of. Putting on a show. It’s a recognition that hopes which ripple from even forced laughter are a reminder of what we have in common. Equally, Dad will have had an eye to the opportunity for tapping his familiar audience. He too is seeking a sense of renewal, affirming what mattered to him about the decades spent together in a palpably lost industrial sphere.

The poem’s time-eroded conclusion strikes a happier note that will accompany us through a second year apart. Until our next reunion, he urges, until next time, be of good cheer because what we made together is not erased. And in submitting his observations to that local newspaper Dad will have been aware that some of the ex-colleagues he bought a beer for will encounter his honest and hopeful portrait over a quiet brew and biscuit.

The work diary and roles my dad inhabited give me a second chance to discover who he was. A show-off, modest and deeply critical too, I have no doubt he hoped it would be me who found this witty, observational account of a job where, aged 50, he was starting again from the bottom. Because he knew I would recognise its value. Perhaps.

I have a pretty wit. I can be merry, wise, quaint, grim,

and sardonic, one by one, or all at once: I know all the

jests – ancient and modern – past, present, and to

come; I can riddle you from dawn of day to set of sun,

and if that content you not, well on to midnight and the

small hours.

Jack Point’s words ring out from behind the bedroom door where Dad practises his lines. Boastful like a jester, pitiful, sometimes a bore or straight good fun, such traits sing out through a diary I have only just begun to traverse.

What single element sums up a life? A simplistic question, but a good test of how hard one has tussled over the possibility of knowing someone more. My response is unquestionably a question mark. In the few years since Dad died I’ve begun to celebrate what he hid, to amplify what he showed to a few and wanted shown to more. These are hesitant greetings of mine. I was not his equal. I was his child.

His listeners, his necessary audience, they helped him to understand himself. If an expert came to the door he was a sponge, soaking up what they had to offer. He was attuned, I’m convinced, to the nuances of A, B and C. An optimist (in private sometimes a disappointed one), he could be relied on to say things to shock, to stir up a dull conversation about shopping or purely for dramatic effect.

He would wheedle out the truth when he sensed someone was lying (perhaps to make a truth more palatable, but that was of no consequence).

He took risks so that he could examine the fall-out, having gamed it.

In some confrontations I’m convinced he was shielding an awareness that others knew more. As a goalie in the factory team he was expert at moving the posts.

Right at the end of his life when he could barely speak you might think it was love Dad sought, not a laugh. Once accepted that there are no more lines, from a double dementia mind he managed to muster two words. I am grateful for these words, and flatter myself that he trusted me with their telling. I wasn’t necessarily his best audience, but it isn’t until I write this story of him that I realise the Covid-isolated care home wasn’t necessarily the worst place to hear his words. It was pure tragedy, but the words made me laugh. They make me laugh.

That Dad never managed to visit the real mountainous panorama of Castle Adamant, meet King Hildebrand, this is not a sadness because it’s a place that exists in a script, where he journeyed many times. I think that in those brief periods of lucidity as he approached death he was able to appreciate how extraordinary a life he’d lived, given the limited opportunities of the start. On the other hand, as an only child of parents who loved him, what better way to believe that anything is possible? I was loved. Anything is possible. I became the writer and artist I set out to be. My parents’ gift was to instill the value of the imagination.

A story can surprise its writer. We may arrive at the end with our readers to find a bigger question waiting. Or, a different question. It lurks behind the door, a door that remains ajar.

Perhaps the last two words my Dad chose to speak meant something entirely different from my interpretation. But I don’t think so.

A writer decides what stays in, what’s left out. Flying in the face of a rash promisory note, a question posed at the beginning will not always be answered by the end. A story that does not reach its anticipated conclusion should not necessarily disappoint. And because this ending-for-now is a trick my dad may well have played, I can choose to play it for him.

From my privileged auricular position I can continue to amplify because I consider who my dad was worthy of amplification. Those last two words he uttered are for another story. Perhaps none. But I will tell you: although his ending was a surprise to me, all he achieved in his life no longer is.

(copyright A.T. Boyle 2025)

The Guardian newspaper obituary for Terry Boyle

The Guardian newspaper obituary for Jean Boyle

_______

About the author

A.T. Boyle is the author of eight short memoir pieces in exObjects: the art of holding on, letting go published in India.

The book contains stories about Preston and Blackpool in Lancashire, England, alongside tales inspired by Bengaluru, Kerala, Kolkata, Scotland and many other places.

A digital version of the first exObjects collection of memoir stories can be bought here

Co-edited by Shinie Antony, this hardback book contains colour images of the objects that inspired the contributions from well-known novelists, scriptwriters, a biographer and short story writers Vikram Sampath, Ramona Sen, Jerry Pinto, Sauma Afreen, Gajra Kottary, Belinda RushJansen, Devasiachan Benny, Shashi Deshpande, Shinie Antony and Jaishree Misra.

The first exObjects book was launched in December 2024 at the Bangalore International Centre in India.

Alongside regular exObjects creative writing workshops (see Events and News page), the book is being brought to the UK and the rest of the world in 2025-26.

One of A.T. Boyle’s short stories in the exObjects book features Terry Boyle in Rogers and Hammerstein’s musical Oklahoma. He is performing the role of Curly in a theatre in Lancashire, northern England.

________

To read the other 5 commissions in Writing that Sings click here